Aged 12, Maryam Zaree discovered she had been born in one of Iran’s most notorious prisons. I spoke to her about her new documentary, Born in Evin, which explores childhood memory and trauma.

When I embarked on this journey as the First 1,000 Days correspondent, I decided to start off by deconstructing memory. My working idea is that we were all once children, yet we remember little of our own first 1,000 days. I wanted to understand whether this phenomenon known as childhood amnesia is what leads us, as adults, to disregard the importance of childhood.

I’ve since looked at how memory works, and next I want to look at how memory is far from being something that is just individual. What we remember, or don’t remember, is often the result of a variety of elements, many of which are political and social. I believe children’s memories matter because what they know or don’t know is frequently a telltale sign of wider political issues.

As part of my research into these themes, I stumbled across actor-director Maryam Zaree and her film Born in Evin*, a story of one woman’s quest to uncover the details of her childhood.

(*Born in Evin is Zaree’s directorial debut film in which she attempts to understand the violent circumstances of her birth)

In the film, Zaree essentially asks: “What does that child know that I don’t?” It is a question that most of us should be able to relate to. Our first two years of life are fundamental to the formation of our brains as well as to our health and development, yet we recall little of that period of our lives. I interviewed Zaree in Berlin in September, before a screening of her film.

I interviewed Zaree at a screening of her film curated by Save the Children for the Human Rights Film Festival.

See their website here.

Maryam Zaree’s search to discover her past

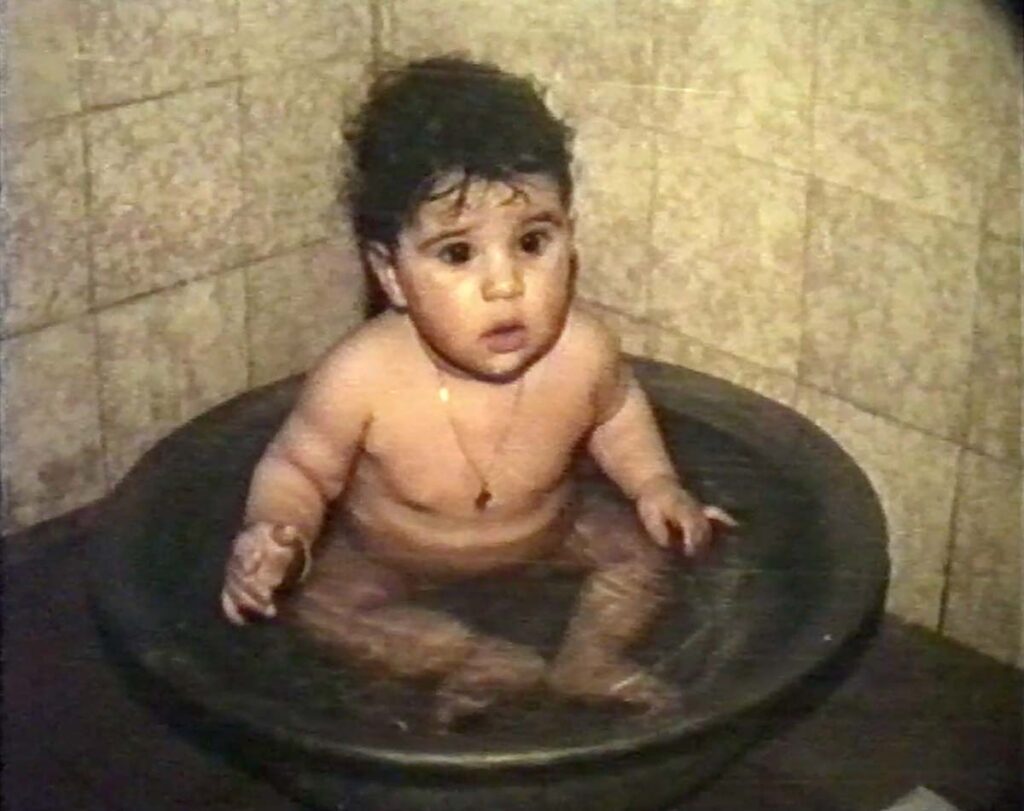

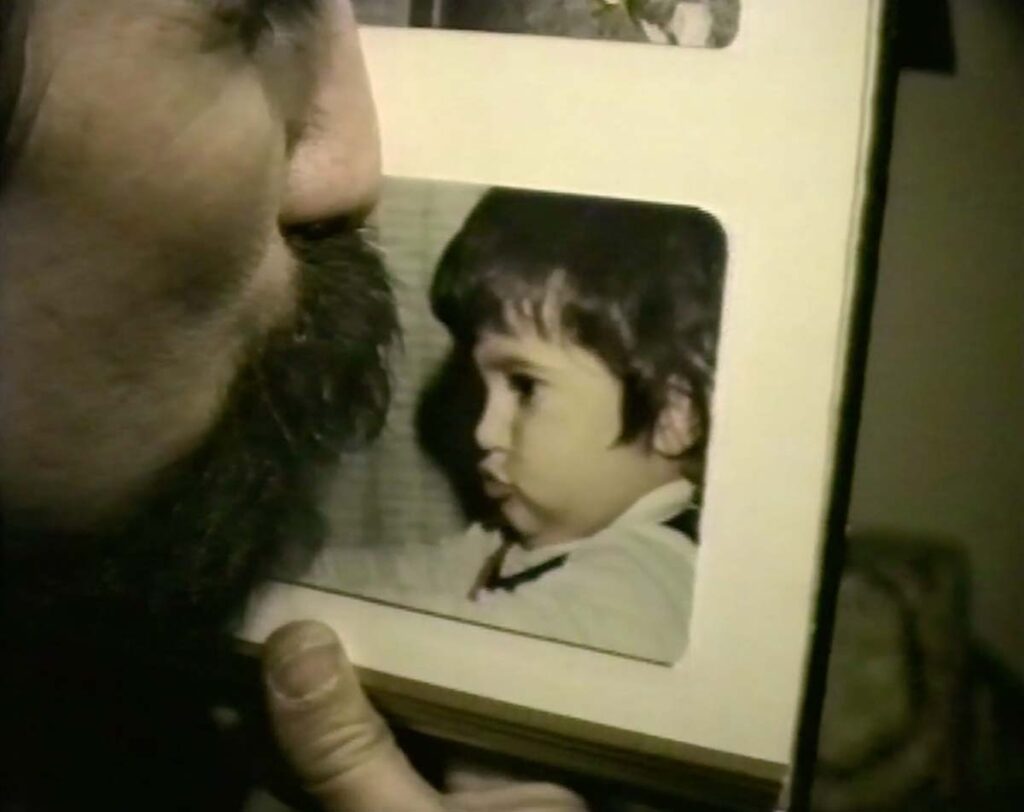

In the earliest surviving photo she has of herself, Zaree is sitting upright in a plastic washbowl full of water – a sort of improvised bathtub – on a shower floor. She is naked, with her chubby arms out of the water and a look of wonderment in her eyes. She is around nine months old in the picture – a little bit older than you’d expect for a first picture from a family that is keen on documenting the passage of time.

Born in Iran in 1983, Zaree’s first memories are of life in Europe, where she arrived at the age of two with her mother. As a child, she knew her father had stayed behind. What she did not know was that both her parents had been political prisoners of the regime of religious leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini*, and that her life had not started in a hospital, or even at home. Zaree was actually born in Iran’s notorious Evin Prison**, months after her mother had been arrested. This is why there are no photographs of Zaree’s first few months.

(*Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini had been a vocal critic of the Shah but support for him and the revolution dwindled over the decades. You can read more about his legacy here.)

(**Evin Prison in Tehran has become notable for hosting political prisoners in aberrant conditions that have been repeatedly denounced by human rights groups. The prison has been used since the 1970s for political purposes, and it remains an active part of the regime crackdown now)

Her parents, Kasra Zaree and Nargess Eskandari-Grünberg, were young idealists who met in Iran. They listened to music by John Lennon and fought for the overthrow of the last Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

(Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was Iran’s monarch, or Shah, between 1941 and 1979, when he was overthrown by popular unrest. The Shah was supported by western powers, especially Britain, and his regime was considered corrupt, undemocratic and brutal.

You can find out more about the buildup to the 1979 revolution in this Al Jazeera documentary.)

In 1979, popular unrest turned into a revolution, and the Shah was forced to leave the country. But the freedom sought by Zaree’s parents and thousands of others never came: Ayatollah Khomeini stepped into power. He declared Iran an Islamic republic and was leader of the western Asian country until his death in 1989.

“The just and free society they were fighting for would soon become their biggest nightmare,” says Zaree in the film. Religious rule was imposed and tens of thousands of political opponents were persecuted, arrested – and, in many cases, killed*. In 1983, Zaree’s parents were imprisoned in Evin – along with the director, who at the time was still in her mother’s belly.

(*In 2012, the Iran Tribunal convened in The Hague to investigate crimes against humanity committed by the Islamic Republic of Iran. Though the tribunal had no legal standing, it was set up by survivors and families of victims living in exile to establish the Iranian government’s systematic role in the execution of up to 20,000 of its citizens.

For more info, click here.)

It was then the family’s silence began. Zaree’s mother never spoke about her pregnancy, her daughter’s birth, or when and why the little girl went to live with her grandparents. Even when Zaree found out where she was born – because her aunt let it slip – and the teenager started asking questions, her mother refused to talk.

Repressed memories begin to surface

What Zaree did know was that on Christmas Eve 1985, she arrived in Frankfurt with her mother thanks to the German government’s refugee programme*. Her mother was only 20 years old at the time.

(*Eskandari-Grünberg is vocal about this migration journey. In the film, there is a scene in which she – the first woman born outside of Germany to run for mayor – retells the anecdote at the Frankfurt central station to launch her campaign.)

The Berlin-based filmmaker grew up receiving letters, audio and video messages from her father in Iran. When she was about 10, she finally met her father, Kasra Zaree: he had spent seven years in prison and was released after surviving the massacre of political prisoners in which thousands of people were executed in 1988.

At 22, Zaree’s repressed memories of her early childhood started to emerge. She was on a bus in Morocco when she started to feel ill and panicky. Eventually, she realised it was the music blasting from the stereo in the bus that was causing her anxiety. Nothing like this had ever happened to her before. She tells me that she screamed at the driver to turn the music off. As soon as he did, she remembers immediately feeling better.

Later, she spoke to her father, who told her that acoustic torture was common in Evin: surahs, or chapters of the Qur’an, were played in an endless loop in the prison, which is most likely what triggered her reaction on the bus.

A few years later, Zaree began looking for other children born in Evin, or in other Iranian prisons, but soon learned that it wasn’t just her family who refused to speak about that time*. But she did come across Sahar Delijani, a writer who was born in Evin, just a few months after Zaree herself. Delijani had written a novel, Children of the Jacaranda Tree, which begins with a description of a birth in a prison.

(*I asked Hamed Farmand, president of non-profit Children of Imprisoned Parents International (COIPI), whether there are figures of how many children were born or held in prison because of political persecution. Farmand, whose mother was also a political prisoner, says there is a lack of information, and many children prefer not to reveal their story. Zaree and Sahar Delijani are exceptions.

Find COIPI’s website here.)

Reading the fictitious account, something clicked for Zaree. She was inspired by the use of art to tackle the subject of her upbringing, and realised that there was more than personal value in exploring her birth story. “Something as exotic as a birth in prison, which I always thought would be particular to my own story, existed on a larger scale,” the director says.

In Born in Evin, Zaree interviews former political prisoners and their children – though many are still reluctant to speak about their experiences. She also interviews Delijani, who tells her that she asked her mother about her own birth in prison once when they were on a plane about to take off. Unable to get away from the difficult questions, Delijani says her mother finally gave her answers.

Zaree also talks to Nina Zandkarimi, a psychologist in London, who as a child had been imprisoned. Zandkarimi remembers later waking up at night with a recurring nightmare: a baby screaming uninterruptedly while a woman was being hit and tortured.

Asking the right questions

Born in Evin recounts Zaree’s journey, but it is far from voyeuristic. Spectators are not given details of Zaree’s parents’ stays in prison, for example, and emphasis is not put on gruesome details or torture. It does, however, put together some of the missing pieces of Zaree’s personal puzzle, as well as those of a wider generation of children of Iran’s political prisoners.

In addition, the director’s questions resonate beyond Iranian politics. Zaree, for example, often mentions the Holocaust, since her stepfather, Kurt Grünberg, is a child of Holocaust survivors and a psychologist working on how trauma can be passed on from one generation to another*. In making these wider connections, Zaree attempts to detach herself – and the viewer – from the personal elements of the story.

(*Kurt Grünberg is a psychologist working at the Sigmund Freud Institute in Frankfurt. Some of his work has focused on the idea of “scenic memory” of the Holocaust. This means that survivors communicate their memories not necessarily verbally, but that the passing on of the trauma happens at an unconscious level.

Here is a link to one of his studies.)

“It’s so interesting. People always refer to the film as being extremely personal, which I disagree with to some extent,” says Zaree. “The personal story is an entry point to expose something much more collective and political. I had no interest in doing a film about myself or my story. At first, I didn’t even appear in it. I worked on the film for over four years. Up and through the editing process, which took a year, we kept asking: is this showing something that is both personal and universal, and where is the point where the two merge?”

Even though memories are personal, they are the result of many elements, including politics. And in many cases, the absence of an explicit memory is equally important.

Finding “closure”, or answers to personal questions, is not what Born in Evin is about, as far as Zaree is concerned. In fact, she hardly gets any answers at all. The film is actually a meditation on asking crucial questions about childhood and the power of our formative experiences over who we later become.

“My biggest fear is to dare to ask you these questions,” Zaree tells her mother in the film, before listing them:

When you got to prison, did you tell them you were pregnant?

Did they kick you in the belly? Were you worried I was dead?

Did you talk to me when I was in your belly?

Is it true that you had to give birth blindfolded and you couldn’t see me then?

Did they torture you, and was I present?

“By finding the courage to put myself and our story in the centre stage, something else can happen with the audience and the spectators on the transference level,” says Zaree. “They can ask questions about denial within their [own] culture, within their country, within their families, and that’s what I care about.

This article first appeared in The Correspondent, the member-funded platform that shut down on 1 January 2021.